When you pick up a generic pill from the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it will? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab terms-they’re the backbone of every generic drug approval in the U.S., Europe, and beyond. If these two values don’t match closely enough between the original drug and the copy, the generic won’t be approved. And that’s not just bureaucracy-it’s safety.

What Cmax Tells You About Drug Absorption

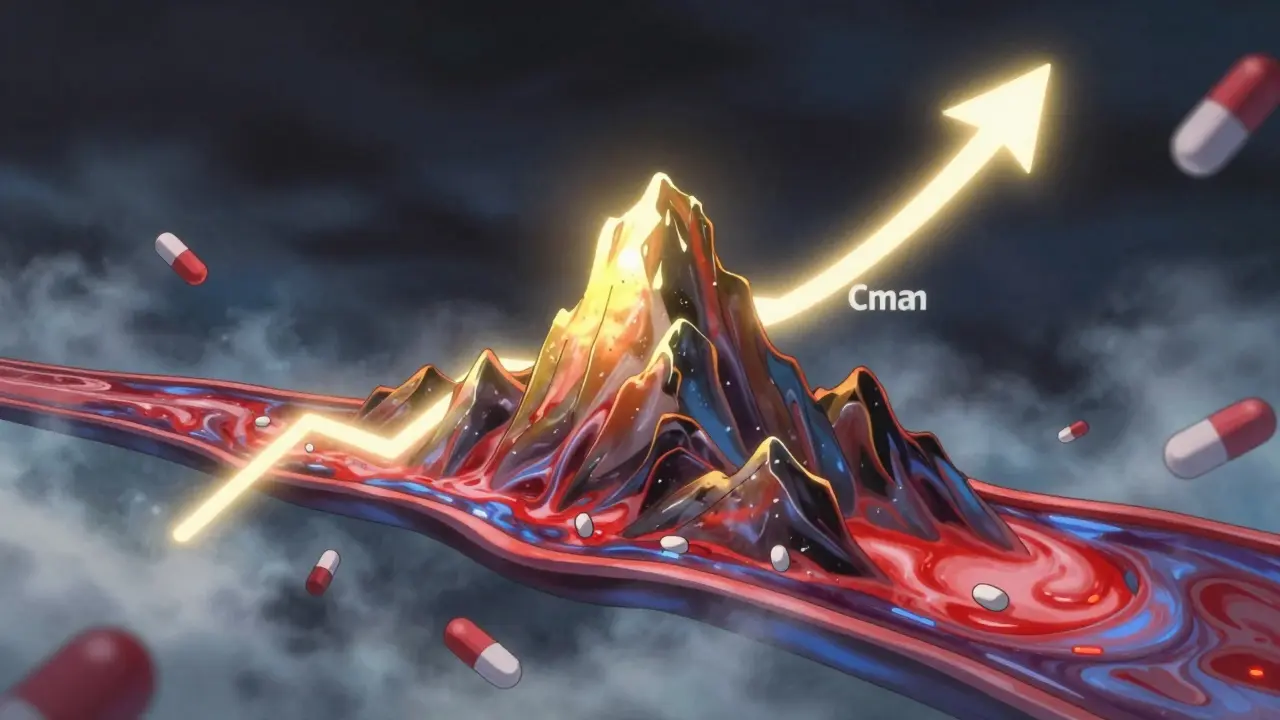

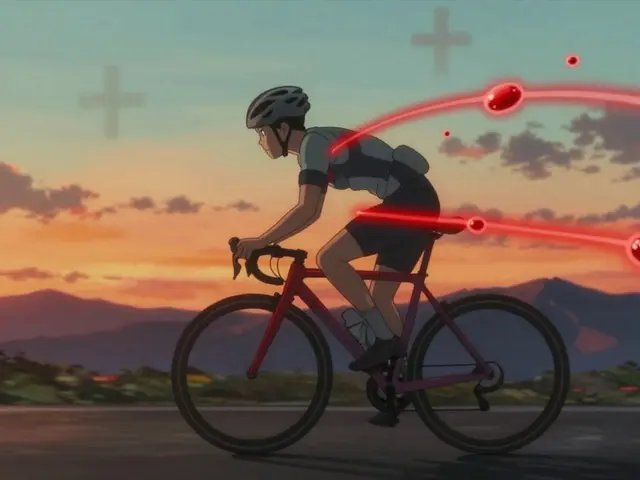

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration. It’s the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph-how high the drug climbs before it starts to fall back down. This number matters because some drugs only work when they hit a certain high point. Take painkillers like ibuprofen: if the peak is too low, you won’t feel relief. But for drugs like digoxin or warfarin, a peak that’s too high can be dangerous-even deadly.

Regulators don’t just look at the number. They also check when it happens-called Tmax, or time to reach Cmax. A generic version might hit the same peak, but if it takes twice as long to get there, it could cause problems. Imagine a fast-acting insulin: if the generic version slowly creeps up instead of spiking quickly, blood sugar could spike dangerously before the drug kicks in.

Studies show that missing the early absorption phase-those first 1 to 2 hours after dosing-is the most common reason bioequivalence studies fail. If blood samples aren’t taken often enough during this window, the Cmax value gets skewed. That’s why modern trials collect blood every 15 to 30 minutes right after dosing, especially for quick-absorbing drugs.

What AUC Reveals About Total Exposure

AUC, or area under the curve, measures the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. It’s like calculating the total area under a mountain’s slope-not just the height, but how long the drug stays in your system. This is critical for drugs that need steady, prolonged exposure to work. Antibiotics like amoxicillin, or antidepressants like sertraline, rely on AUC to ensure they stay above the minimum effective level long enough to kill bacteria or balance mood.

AUC is measured in units like mg·h/L. A value of 120 mg·h/L means the drug averaged 120 milligrams per liter in your blood over one hour, cumulatively. If a generic drug delivers only 85% of that total exposure, your body might not get enough to work properly-even if the peak looks fine.

There are different types of AUC used in testing: AUC(0-t) covers the time until the last measurable concentration, and AUC(0-∞) estimates total exposure including what’s cleared after the last sample. For most drugs, AUC(0-t) is enough. But for slow-clearing drugs, researchers need to extrapolate to infinity using mathematical models.

The 80%-125% Rule: Why This Range Exists

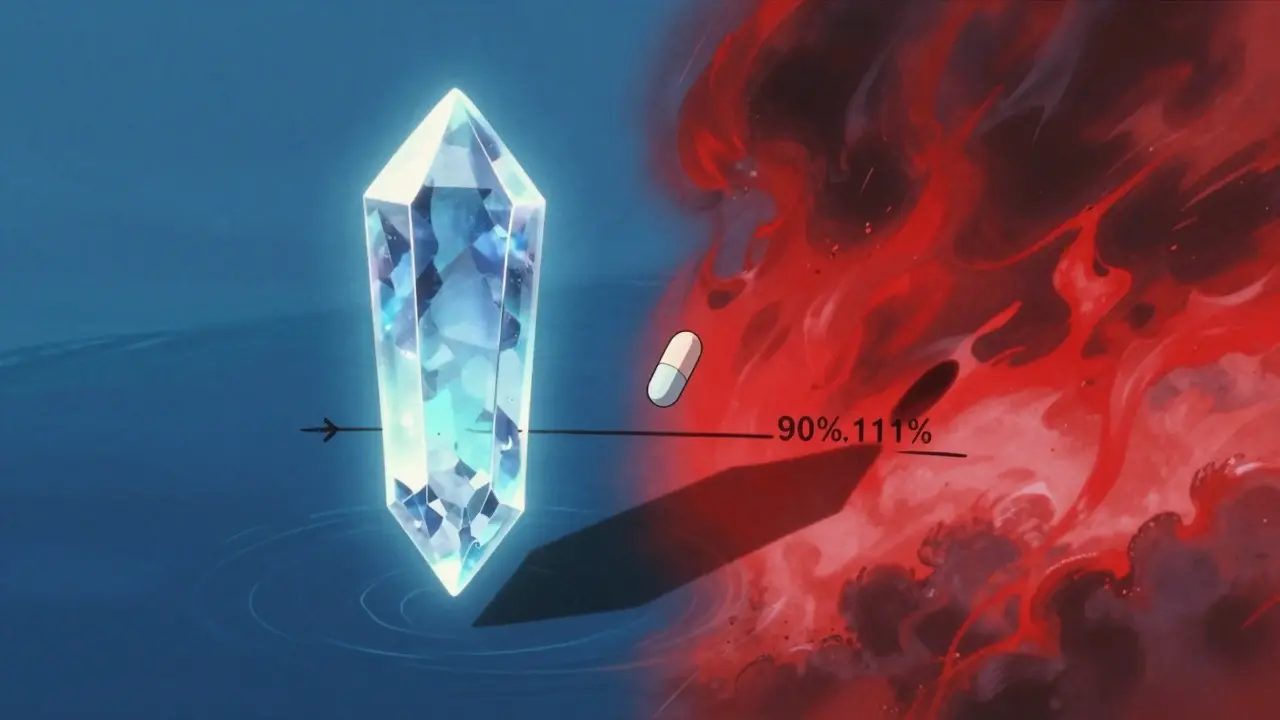

Here’s the deal: regulators don’t demand identical numbers. They allow a range. For both Cmax and AUC, the ratio of the generic to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand’s Cmax is 10 mg/L, the generic’s must be between 8 and 12.5 mg/L. The same applies to AUC.

This range wasn’t picked randomly. It came from decades of clinical data and statistical modeling. In the early 1990s, experts realized that differences under 20% rarely caused real-world problems. They converted the 80%-125% range into logarithmic scale (ln(0.8) = -0.2231, ln(1.25) = 0.2231) because drug concentrations follow a log-normal distribution-not a straight bell curve. This makes the math more accurate.

And here’s the kicker: both Cmax and AUC must pass this test. One failing means the whole study fails. You can’t say, “Well, AUC is fine, so the drug’s good.” No. If Cmax is 75%, the generic gets rejected-even if the total exposure is perfect. Why? Because the rate of absorption affects how quickly the drug acts-and that can change side effects or effectiveness.

When the Rules Get Tighter: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

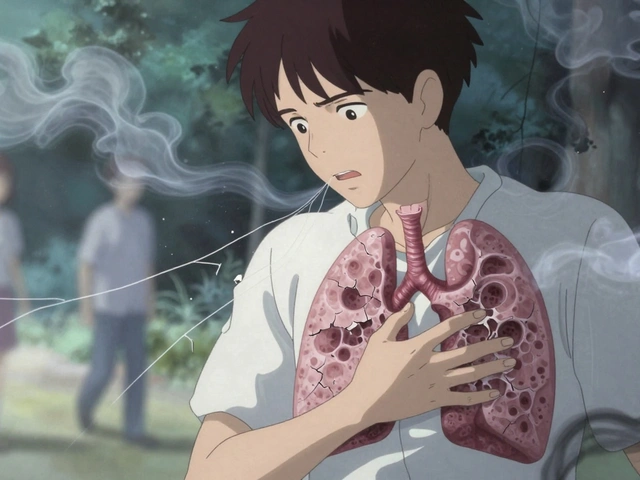

Not all drugs are created equal. Some, like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine, have a narrow therapeutic index. That means the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny. For these, the standard 80%-125% range is too loose.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA now recommend tighter limits-90% to 111%-for certain high-risk drugs. Why? Because a 15% drop in exposure could make warfarin ineffective and cause a clot. A 15% increase could cause bleeding. In one 2021 study analyzing 500 bioequivalence trials, nearly 20% of narrow-index drugs had Cmax ratios outside the 90%-111% range, even if they passed the standard test.

Some manufacturers push back, arguing that stricter limits block good generics. But regulators say: better safe than sorry. For these drugs, even small differences can mean hospital visits. That’s why many pharmacies now track which generic brand you’re on-and stick with it.

How Bioequivalence Studies Actually Work

These aren’t just lab experiments. They’re tightly controlled clinical trials. Typically, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers take both the brand-name and generic versions, in random order, with a washout period in between. Each participant gets blood drawn 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours-depending on how long the drug lasts.

Modern labs use LC-MS/MS machines to detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s like finding a grain of salt in an Olympic-sized pool. These tools make it possible to test even tiny-dose drugs like levothyroxine (25-200 micrograms) with precision.

Statistical analysis uses log-transformed data to calculate the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means. Most companies use software like Phoenix WinNonlin or SAS to run these analyses. It takes 2-3 days per study. About 85% of submissions use the standard two-period crossover design. The rest? They’re usually for complex drugs-like extended-release tablets or inhalers-where the rules are still being refined.

Why This System Works-And Why It’s Here to Stay

Since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, over 1,200 generic drugs get approved in the U.S. every year. Almost all rely on Cmax and AUC. And here’s the proof it works: a 2019 meta-analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that passed bioequivalence testing.

Even with new tech like AI modeling and population pharmacokinetics on the horizon, Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard. Why? Because they’re simple, measurable, and clinically meaningful. You can’t fake them. You can’t game them. And they’ve been validated across millions of patient-years of real-world use.

Regulators in 120+ countries use this same framework. The World Health Organization calls it the “cornerstone” of global medicine access. It’s how a person in Kenya can get the same heart medication as someone in London-for a fraction of the price.

What’s Changing? The Future of Bioequivalence

There’s talk about using partial AUC (pAUC) for drugs with multiple absorption peaks-like some extended-release pain meds. The FDA is exploring whether modeling can reduce the number of human trials needed. But these are supplements, not replacements.

For now, if you’re developing a generic drug, your first step isn’t chemistry. It’s designing a study that captures Cmax and AUC accurately. Miss the sampling window? Your drug won’t get approved. Get the numbers wrong? You’ll waste millions.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s the best we’ve got. And for patients, that’s what matters.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. In bioequivalence studies, it measures how quickly a generic drug is absorbed compared to the brand-name version. If the peak is too low or too high, or if it happens at a different time, the drug may not work the same way.

Why is AUC important in bioequivalence testing?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It tells regulators how much of the drug your body actually absorbs and keeps in circulation. For many medications-like antibiotics or antidepressants-this total exposure determines whether the drug will be effective. A generic must deliver a similar total amount as the original to be considered equivalent.

What is the 80%-125% bioequivalence range?

The 80%-125% range is the legal limit for how different a generic drug’s Cmax and AUC can be from the brand-name version. Both values must fall within this range for approval. This range is based on decades of data showing that differences smaller than 20% are unlikely to affect safety or effectiveness in most cases. The range uses logarithmic scale to account for how drug concentrations naturally vary in the body.

Do both Cmax and AUC need to pass the bioequivalence test?

Yes. Both Cmax and AUC must independently meet the 80%-125% criteria. Even if one passes and the other fails, the entire bioequivalence study is rejected. This is because Cmax reflects absorption speed (important for side effects and onset of action), while AUC reflects total exposure (important for overall effectiveness). One can’t substitute for the other.

Are there exceptions to the 80%-125% rule?

Yes-for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine, regulators require tighter limits: 90% to 111%. These drugs have a very small window between a safe dose and a toxic one, so even small differences in exposure can be dangerous. Some countries also allow scaled bioequivalence for highly variable drugs, but this requires extra data and justification.

How are Cmax and AUC measured in practice?

In a bioequivalence study, healthy volunteers take both the brand and generic versions, with blood samples taken frequently-often every 15-30 minutes in the first few hours. Labs use ultra-sensitive LC-MS/MS machines to measure drug concentrations as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. The data is then analyzed using log-transformed ratios and 90% confidence intervals to determine if both Cmax and AUC fall within the required range.

So I’ve been on levothyroxine for like 12 years now, and I swear by the same generic brand. My endo told me once that switching brands even slightly can mess with my TSH levels-like, tiny changes, but enough to make me feel like a zombie for a week. I don’t get why people think generics are all the same. They’re not. The fillers, the coating, the release rate-it all adds up. I just stick with what works and ignore the hype.

Also, I once tried a cheaper one because my insurance switched, and I had heart palpitations for three days. Never again. Cmax isn’t just a number-it’s how your body feels at 3 a.m. when you can’t sleep because your thyroid is throwing a tantrum.

Ah, the sacred algorithm of bioequivalence-80% to 125%-a numerical liturgy whispered in the cathedrals of Big Pharma and its acolytes in regulatory agencies. We’ve been conditioned to believe that this range is the divine midpoint between safety and efficacy, but isn’t it just a statistical illusion dressed in lab coats?

What if the body doesn’t care about geometric means? What if it cares about rhythm? About the *soul* of absorption? AUC is a corpse’s ledger; Cmax is the heartbeat. We reduce living pharmacokinetics to two digits on a spreadsheet and call it science. The real question isn’t whether the numbers match-it’s whether we’ve forgotten what medicine is for: to heal, not to quantify.

And yet… I still take the generic. Because what else can we do when the system is the only game in town?

Man I had no idea how much science goes into generic drugs. I just grab the cheapest one and go. But now I’m curious-do you think the same testing applies to stuff like ibuprofen or allergy meds? Like, is the difference even real or just a regulatory checkbox?

Also, I work in pharma logistics and we ship tons of these generics. The machines they use to test blood levels? Insane precision. Like detecting a grain of salt in a lake. Wild.

Anyway, props to the folks running these studies. We need more transparency like this. Keep it real.

Oh, here we go again. The ‘80%-125% rule’-a euphemism for ‘we’re too lazy to demand exactness.’ You think this is science? It’s corporate compromise. And let’s not pretend that ‘narrow therapeutic index’ drugs are the only ones at risk. What about antidepressants? Anticonvulsants? Even a 10% drop in sertraline exposure can trigger withdrawal symptoms that feel like a nervous system meltdown.

And don’t get me started on the sampling windows. If you’re only checking blood every 30 minutes for a fast-acting drug, you’re missing the peak entirely. It’s like measuring a lightning strike with a sundial.

Regulators aren’t protecting patients-they’re protecting the bottom line. And patients? We’re the guinea pigs who just hope the pill doesn’t kill us.

It’s fascinating how such a technically precise methodology-log-transformed 90% confidence intervals, LC-MS/MS detection limits at sub-nanogram levels-is used to regulate something as inherently variable as human physiology. The system assumes uniform absorption, uniform metabolism, uniform response. But we are not test tubes.

And yet, the data holds. The JAMA meta-analysis is compelling. Millions of patient-years, no meaningful difference. So while the philosophy of reductionism is troubling, the empirical outcome is reassuring. Perhaps the system works not because it’s perfect, but because it’s robust enough to tolerate our biological chaos.

Still… I wonder how many patients are silently suffering from suboptimal generics because their Cmax is 81% and they just feel ‘off’-but no one checks.

Why are we letting foreign labs and overseas manufacturers make our medicine? This whole Cmax AUC thing is just a cover for letting China and India dump cheap pills into our system. They don’t follow the same rules. They don’t care about our people. We’re letting our health be outsourced to sweatshops with lab coats.

And now you want me to believe that 80% is good enough? What if that 20% is what keeps my heart from stopping? This isn’t science-it’s surrender.

Buy American. Demand American-made generics. Or you’re putting your life in the hands of communist factories.

In India, we’ve been making generics for decades-cheaper, accessible, life-saving. But we’ve also seen the flip side: when quality slips, people suffer. I’ve seen patients on antiretrovirals whose viral loads spiked after switching generics-not because the active ingredient changed, but because the excipients altered absorption.

So yes, Cmax and AUC matter. But what matters more is consistent manufacturing standards. India’s FDA-equivalent (DCGI) now requires bioequivalence for all generics, and it’s made a huge difference. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s a step toward equity.

And honestly? The fact that a kid in Nairobi gets the same HIV meds as a CEO in London? That’s the real win. Not the math. The humanity.

Let’s be real: the entire bioequivalence framework is a glorified pharmacokinetic bingo card. You hit Cmax, you hit AUC, you hit the 90% CI, you win a generic approval. But here’s the kicker-no one’s tracking long-term clinical outcomes post-approval. We assume equivalence because the curves look similar.

But what about drug interactions? What about gut microbiome variability? What about epigenetic differences in metabolism? We’re treating humans like single-compartment models. We’re not even scratching the surface.

AI-driven population PK models are coming. They’ll let us simulate thousands of virtual patients. Until then? We’re flying blind with a ruler and a prayer.

This is why you can't trust generics. They cut corners. Always have. Always will.