When you pick up a prescription for a generic drug, you’re benefiting from a decades-old legal balancing act designed to keep drug prices low and competition alive. But behind the scenes, a quiet war is being fought-between big pharma and generic makers-over who gets to sell cheap versions of life-saving medicines. Antitrust laws are supposed to ensure fair play, but in the generic drug market, they’re often the only thing standing between consumers and inflated prices.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Foundation of Generic Competition

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. It was meant to be a win-win: branded drug companies got extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval, while generic manufacturers got a faster, cheaper path to market. The key? The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Instead of repeating expensive clinical trials, generics could prove they were bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That cut development costs by 80% or more.

The law also gave the first generic company to challenge a patent a 180-day exclusivity window. That’s a huge incentive. If you’re the first to file a Paragraph IV certification-claiming a patent is invalid or not infringed-you get to be the only generic on the market for half a year. That’s when prices drop hardest. The FTC says that single generic entry can slash prices by 20% in a year. Add five competitors, and you’re looking at nearly 85% of the original price gone.

By 2016, generics made up 90% of all U.S. prescriptions. Between 2005 and 2014, they saved consumers $1.68 trillion. In 2012 alone, Americans saved $217 billion. That’s not just a number-it’s people who can afford insulin, blood pressure meds, or cancer drugs because generics exist.

How Big Pharma Blocks Generic Entry

But not everyone plays by the rules. The same system designed to promote competition has been exploited. One of the most notorious tactics is pay-for-delay. Here’s how it works: a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to stay out of the market. Instead of fighting the patent in court, the generic gets a check to delay its launch. The FTC calls these reverse payments. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals could violate antitrust laws-if the payment is large and unexplained.

One of the biggest cases? Gilead Sciences paid $246.8 million in 2023 to settle allegations it used pay-for-delay to block generic versions of its HIV drug Truvada. That’s not an outlier. Between 2000 and 2023, the FTC brought 18 pay-for-delay cases. Settlements totaled over $1.2 billion.

Then there’s product hopping. When a patent is about to expire, a company tweaks the drug slightly-changes the pill shape, adds a coating, switches from a tablet to a capsule-and markets it as a “new and improved” version. Patients are switched over, often without realizing it. The original drug becomes harder to get. Generics can’t enter because the old version is no longer available. AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec and Nexium. Courts didn’t find it illegal, but the FTC still calls it a tactic to delay competition.

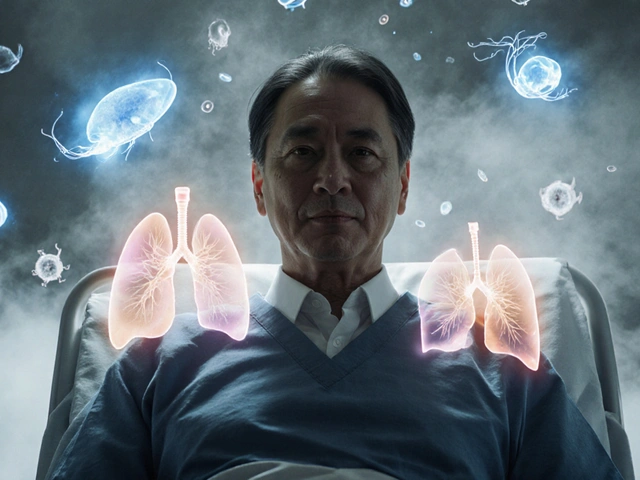

Sham citizen petitions are another trick. Companies file bogus complaints with the FDA, claiming safety or efficacy issues with a generic drug. The FDA has to respond, which delays approval. Teva Pharmaceuticals is currently being sued for filing dozens of these petitions to block generic versions of its multiple sclerosis drug Copaxone. The case is still pending, but the FTC says it’s a textbook example of abuse.

Orange Book Manipulation and Patent Thickets

The FDA’s Orange Book lists all patents covering a brand-name drug. Generic companies must certify against every one. If a company lists patents that don’t actually cover the drug-or files them late-they can delay generic entry. That’s what Bristol-Myers Squibb did in the early 2000s, listing patents for a drug’s inactive ingredients to block competitors. The FTC fined them $1.5 million in 2003. That case set a precedent: listing patents you know are irrelevant is illegal.

Then there’s patent thickets-dozens, sometimes hundreds, of overlapping patents on one drug. It’s not about protecting innovation. It’s about creating a legal maze. Generic companies can’t afford to challenge them all. Even if they win one, another patent pops up. The result? Years of delay. The European Commission found that 60% of its pharmaceutical antitrust cases from 2018 to 2022 involved tactics to delay generic entry. In the U.S., 74% of antitrust cases in pharma involve R&D and manufacturing practices tied to these delays.

Global Enforcement: How Other Countries Fight Back

The U.S. isn’t alone in this fight. The European Union has been aggressive. The European Commission has fined companies for withdrawing marketing authorizations in certain countries to block generic imports. Some firms even misled patent offices to extend protection. In 2023, Commissioner Margrethe Vestager said delays in generic entry cost European consumers €11.9 billion a year.

China moved fast in 2025, releasing new Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector. They identified five “hardcore restrictions” that are automatically illegal: price fixing, output limits, market division, joint boycotts, and blocking new tech. By Q1 2025, six cases had been penalized-five of them involved price fixing through messaging apps and algorithms. Chinese regulators are now using AI to track suspicious pricing patterns in real time.

One lesser-known tactic? Disparagement campaigns. Brand-name companies spread false or misleading claims about generics-saying they’re less effective, have more side effects, or aren’t “real” drugs. Pharmacists get letters. Doctors get emails. Patients get scared. A 2020 study found this reduces generic use even when the science says otherwise. The European Court of Justice has called this a form of anti-competitive behavior.

Who Pays the Price?

Behind every delayed generic, there’s a person skipping doses. A 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found 29% of U.S. adults didn’t take their medication as prescribed because they couldn’t afford it. That’s not just a health crisis-it’s an economic one. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generic competition cuts drug prices by 30% to 90%. When generics are blocked, prices stay high. And when prices stay high, people suffer.

It’s not just about money. It’s about access. Insulin. Blood thinners. Antidepressants. These aren’t luxury items. They’re necessities. When antitrust enforcement fails, the cost isn’t just measured in dollars-it’s measured in hospital visits, missed work, and lives cut short.

What’s Next?

Enforcement is getting smarter. The FTC’s 2022 workshop on generic entry after patent expiration highlighted new red flags: digital collusion, algorithmic pricing, and “authorized generics”-where the brand-name company launches its own cheap version to crush competitors before real generics arrive.

Legislators are pushing for change. Bills in Congress aim to ban pay-for-delay outright, require transparency in Orange Book listings, and limit the number of patents a company can list. Some states are even creating public databases to track generic entry delays.

The system still works-most of the time. But the loopholes are wide enough for billions to slip through. The real test isn’t whether antitrust laws exist. It’s whether they’re enforced with enough speed, power, and courage to protect the people who need cheap medicine the most.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drugs in the U.S. It lets generic manufacturers use the FDA’s Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to prove their drugs are bioequivalent to brand-name versions, skipping expensive clinical trials. It also gives the first generic company to challenge a patent 180 days of market exclusivity. This system cut drug development costs and helped generics rise from 19% of prescriptions in 1984 to 90% by 2016.

What are pay-for-delay agreements and why are they illegal?

Pay-for-delay agreements happen when a brand-name drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. These are called reverse payments because the generic gets paid to stay out of the market. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals can violate antitrust laws if the payment is large and unexplained. They reduce competition and keep prices high, costing consumers billions each year.

How do companies use the Orange Book to block generics?

The FDA’s Orange Book lists patents covering a brand-name drug. Generic companies must address each patent before entering the market. Some brands list patents that don’t actually cover the drug’s active ingredient-like patents for packaging or inactive ingredients. This delays generic approval. The FTC has fined companies like Bristol-Myers Squibb for this practice, calling it an anti-competitive abuse of the system.

What is product hopping and is it illegal?

Product hopping is when a drug company slightly changes a medication-like switching from a tablet to a capsule-just before its patent expires and pushes patients to the new version. The old version is then discontinued, making it harder for generics to enter. Courts have not ruled this illegal outright, as in the AstraZeneca Prilosec/Nexium case, but the FTC considers it a tactic to delay competition and harm consumers.

How is China tackling antitrust issues in generic drug markets?

In January 2025, China released new Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector that identify five “hardcore restrictions” as automatically illegal: price fixing, output limits, market division, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. By Q1 2025, six cases had been penalized, five involving price fixing through messaging apps and algorithms. Chinese regulators are now using AI to monitor pricing patterns and detect collusion in real time.

What You Can Do

You can’t change antitrust laws-but you can demand transparency. Ask your pharmacist if a generic is available. Check if your insurance covers the generic version. Support legislation that bans pay-for-delay and limits Orange Book abuse. When you choose a generic, you’re not just saving money-you’re helping keep the system honest.

so like... big pharma is just playing monopoly with our insulin?? 😒

in india we get generics for like 1/10th the price but even then some companies drag their feet. same game, different continent. 🤷♀️

the real tragedy isnt the pay for delay its that we celebrate the system working when its barely working at all. we call this capitalism but its just rent seeking with a stethoscope

the hatch-waxman act was a classic case of regulatory capture. the 180-day exclusivity window is a perverse incentive structure that incentivizes litigation over innovation. the economics are clear: monopolistic rents persist through strategic patent aggregation. you can't fix this with band-aids.

so... they pay generics to NOT sell drugs?? and courts are like "eh, maybe"?? 🤡🤡🤡 this is why i don't trust systems designed by lawyers with private jets

The structural impediments to generic market entry represent a significant failure of regulatory oversight. The aggregation of patent portfolios, coupled with the strategic manipulation of administrative procedures, undermines the foundational principles of competitive equilibrium in pharmaceutical markets.

if you can afford it get the brand. if you can't get the generic. either way you're voting with your wallet. and if you're mad? tell your rep to ban pay for delay already

The FTC's 2022 workshop identified algorithmic collusion as an emerging antitrust concern in pharmaceutical markets. Real-time price monitoring via AI, as implemented in China, demonstrates a viable regulatory pathway. Transparency in Orange Book listings remains the most actionable reform priority.

i just lost my job last year and my copay for my antidepressants went from 10 to 85 and i swear to god if i had to choose between eating and taking my meds i dont know what id do and its not fair its not right and no one seems to care except the people who make billions off this and i just want to cry because i know i'm not alone and i know this is happening to millions and no one is doing anything and i just want to scream

they call it "product hopping" like its some cute little dance. its corporate arson. they torch the old version so you gotta buy the new one. and the FDA just watches like its a reality show. 🤬

i just found out my blood pressure med is generic and i was like wait is this the same thing?? and then i looked it up and its literally the same chem but i was scared to take it because of all the hype and now i feel dumb

i used to work at a pharmacy and every day people would ask if the generic was "good enough". i'd say yes, but then they'd look at me like i was lying. we need to fix the narrative, not just the laws. people deserve to trust their meds.

The legislative proposals currently under consideration in Congress to mandate transparent Orange Book disclosures and prohibit reverse payment agreements represent a necessary corrective to systemic market distortions. Such reforms, if enacted with robust enforcement mechanisms, may restore the competitive equilibrium envisioned by the Hatch-Waxman Act.