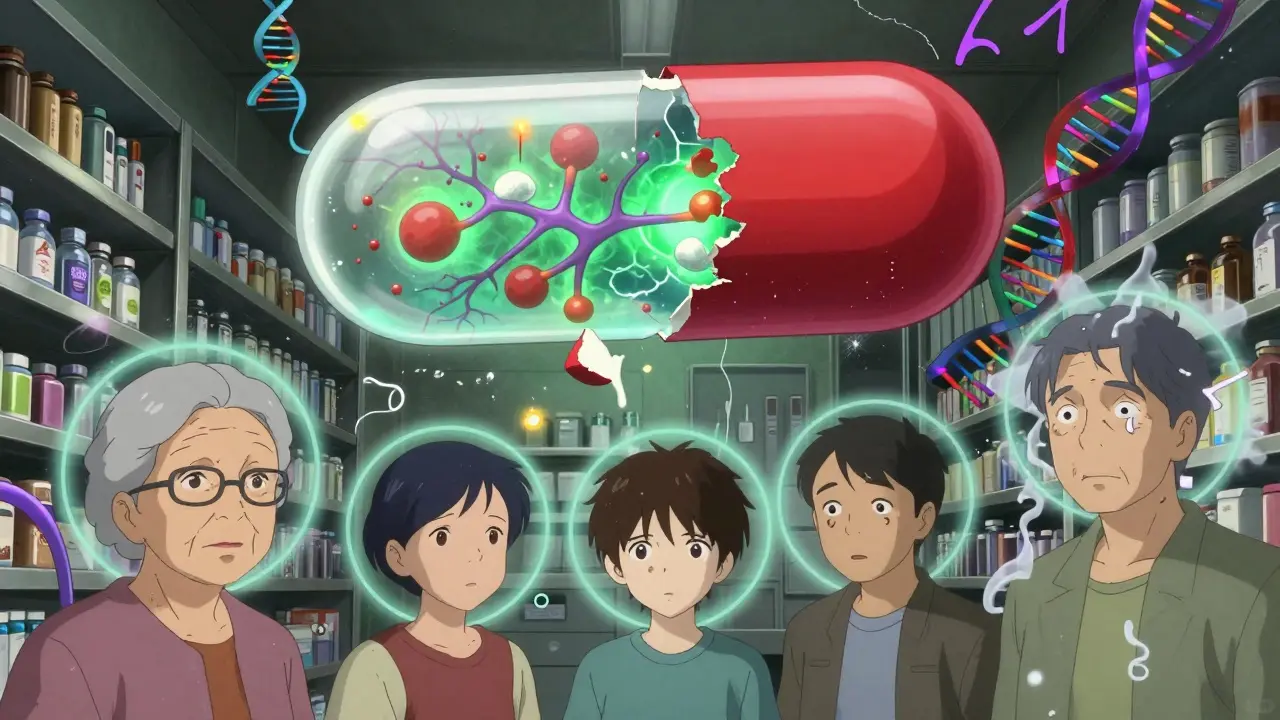

Most people assume that when they take a pill, the only thing that matters is the active ingredient-the drug itself. But what if the rest of the pill, the stuff you’ve never heard of, could change how well it works-or even make you sick? That’s the reality with excipients, the so-called "inactive" ingredients in medications. They make up 60% to 99% of a pill’s weight. They help it hold its shape, dissolve in your gut, taste less awful, or stay stable on the shelf. But calling them "inactive" is starting to look more like a myth than a fact.

What Exactly Are Excipients?

Excipients are everything in your medicine that isn’t the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Think of them as the supporting cast: fillers like lactose or microcrystalline cellulose, binders like polyvinylpyrrolidone, disintegrants like croscarmellose sodium, lubricants like magnesium stearate, and even artificial colors like tartrazine. These aren’t random additives-they’re carefully chosen to make sure the drug gets where it needs to go in your body, at the right speed, and stays safe over time. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lists about 1,500 approved excipients across all routes of administration-oral, injectable, eye drops, ear drops, and more. Each drug typically uses 5 to 15 of them. For decades, regulators and manufacturers assumed these ingredients were biologically neutral. That’s why generic drug makers can swap out excipients without proving they work the same way-unless the drug is injected, put in the eye, or used in the ear. For those, exact matches to the brand-name version are required. For pills? Not so much.Why "Inactive" Might Be a Dangerous Misnomer

A groundbreaking 2020 study in Science turned this assumption upside down. Researchers tested 314 common excipients against 44 biological targets-receptors, enzymes, and proteins in the human body. Thirty-eight of them showed measurable activity. Some were strong enough to interfere with key processes. Aspartame, for example, blocked the glucagon receptor at concentrations you might actually reach after taking a daily pill. Sodium benzoate, a preservative found in many liquid medications, inhibited monoamine oxidase B, an enzyme linked to Parkinson’s and mood regulation. Propylene glycol, used to dissolve drugs and improve absorption, affected monoamine oxidase A, which plays a role in serotonin and norepinephrine breakdown. The kicker? These weren’t just lab findings. In real human bodies, after normal dosing, concentrations of these excipients reached levels that overlapped with their biological activity thresholds. That means what we thought was harmless filler might actually be interacting with your biology in ways we never measured before. The FDA itself acknowledged this in a 2022 guidance: "The assumption of inertness for excipients may not hold for all compounds at all concentrations." That’s not a minor footnote. It’s a crack in the foundation of how we approve medicines.When Excipients Change, So Can Your Response to Medicine

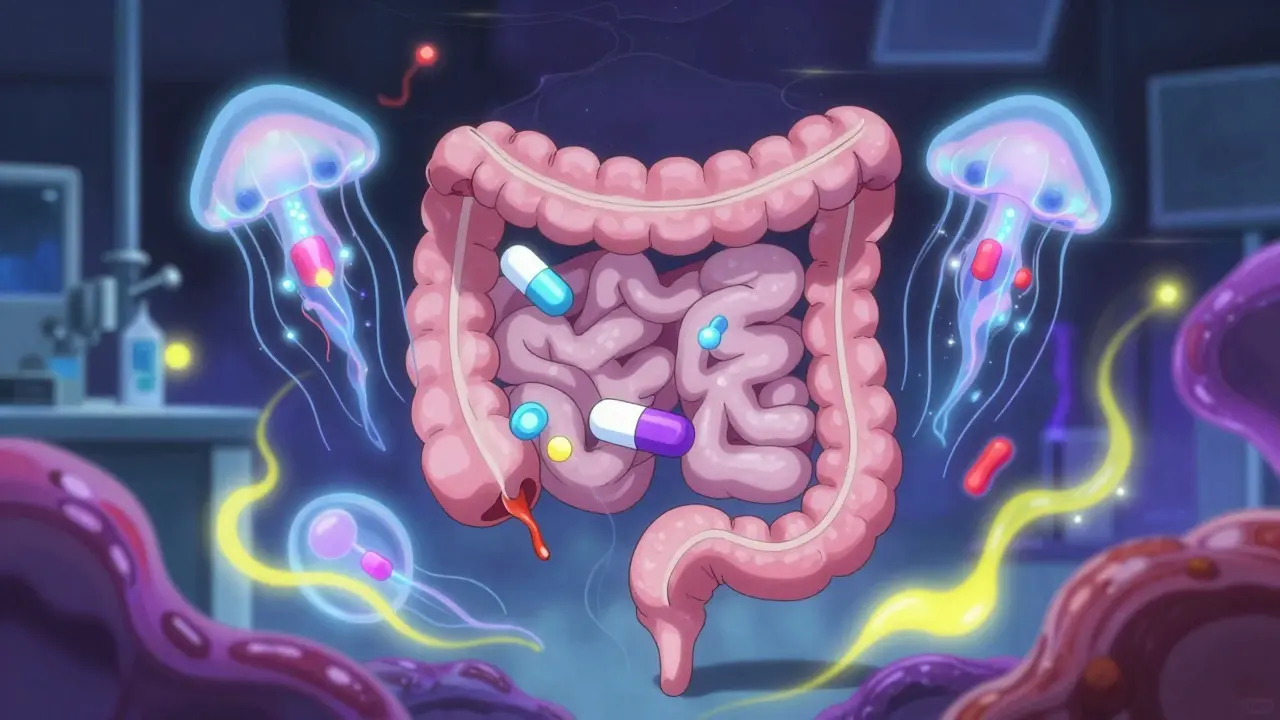

Generic drugs are supposed to be identical to brand-name versions in effectiveness and safety. But they don’t have to have the same excipients-unless they’re injected or used in sensitive areas. That means two pills with the same active ingredient can behave differently in your body because of what’s holding them together. Take the case of Aurobindo’s attempt to make a generic version of Entresto (sacubitril/valsartan). The FDA rejected it because they swapped magnesium stearate for sodium stearyl fumarate. In vitro tests showed a 15% difference in how fast the drug released at pH 6.8-the kind of environment found in parts of the small intestine. Even a small change in dissolution rate can mean the difference between a drug working properly and failing to reach therapeutic levels. On the flip side, Teva’s generic version of Jardiance (empagliflozin) succeeded because they replaced sodium starch glycolate with croscarmellose sodium as a disintegrant. Bioequivalence studies showed near-identical blood levels: Cmax was 374 vs. 368 ng/mL, and AUC was 4,215 vs. 4,187 ng·h/mL. That’s within the 80-125% window the FDA accepts for generics. The difference in excipients didn’t matter-because they tested it. The problem? Most generic manufacturers don’t test. They rely on the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID), which lists excipients that have been used safely before. If your excipient is on the list and at the same concentration, you’re golden. But if you’re using a new one-or an old one at a new level-you need toxicology studies. That costs $1.2 million and takes 18 months on average.

Regulatory Gaps and Real-World Risks

The FDA’s system works fine for simple pills. But it’s falling apart for complex drugs-extended-release formulations, orally disintegrating tablets, combination therapies. These newer products rely on novel excipients to control how the drug is released. And those excipients? They’re not always well-studied. In 2018, 14 generic versions of valsartan were recalled because of NDMA contamination. That wasn’t the active ingredient-it was a solvent used in manufacturing. The excipient system didn’t catch it because regulators weren’t looking at impurities from new processing methods. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is stricter. They require manufacturers to justify every excipient difference in a Quality Overall Summary. The FDA doesn’t. That’s why 17% of generic drug applications get rejected in the U.S.-mostly because companies can’t prove their excipient swap won’t hurt safety or efficacy. And it’s not just generics. Even brand-name drugs are changing. Eighty-seven percent of new molecular entities now include novel excipients to improve delivery. That’s a huge shift. We’re using more complex chemistry to make drugs work better-but we’re still treating the supporting ingredients like afterthoughts.Who’s at Risk?

You might think, "I’m healthy, so it doesn’t matter." But certain groups are more vulnerable. People with allergies: Tartrazine (yellow dye #5) and sulfites in some injectables can trigger reactions-even in people who’ve never had them before. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program is now requiring extra safety data for aspartame and saccharin in orally disintegrating tablets after reports of hypersensitivity. People on multiple medications: Excipients can interact with other drugs. Propylene glycol, for example, can compete with alcohol metabolism. In someone taking multiple meds, that could lead to unexpected side effects. Elderly patients and children: Their bodies process substances differently. A dose of excipient that’s safe for a 30-year-old might be too much for a 70-year-old with reduced kidney function. People with rare genetic conditions: Some people metabolize compounds differently. A preservative like sodium benzoate might be harmless to most-but problematic for someone with a mitochondrial disorder.

What’s Changing-and What’s Next?

The FDA is finally catching up. In 2023, they proposed updating their Inactive Ingredient Database to include predicted tissue concentrations for each excipient. That means they’ll know not just "what’s in the pill," but "where it goes in your body." They’re also developing a computational model to predict which excipients might interact with biological targets-based on the 2020 Science study. The International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council (IPEC) is pushing for concentration thresholds below which excipients can be assumed inert. But critics argue that’s too simplistic. People vary too much. What’s safe for 99% might still harm 1%. The biggest change coming? A proposed amendment to FDA regulations that would require all new excipients to be screened against 50 high-risk biological targets before approval. That could add $500,000 to $1 million to development costs per new ingredient. It’s expensive. But it’s also necessary.What You Can Do

You can’t control what’s in your medication-but you can ask. If you’ve had unexplained side effects after switching to a generic, or if you’ve noticed changes in how a drug works for you, talk to your pharmacist. Ask: "Was the excipient formula changed?" Pharmacists have access to databases that track excipient differences between brand and generic versions. They can flag potential issues before you take the new pill. Also, if you have known allergies or sensitivities, check the full ingredient list on the packaging. It’s required by law. Don’t assume "inactive" means harmless. Sodium benzoate, aspartame, and propylene glycol are all listed on labels-and they’re not harmless to everyone.The Bottom Line

Excipients aren’t just filler. They’re functional, sometimes active, components of your medicine. The idea that they’re all safe and inert is outdated-and potentially dangerous. Regulatory systems are slowly waking up to this reality. But until they fully modernize, the burden falls on patients and prescribers to stay informed. Your pill might look the same. But if the excipients changed, your body might respond differently. That’s not a technicality. It’s a matter of safety and efficacy-and it’s time we stopped treating it like one.Are excipients really inactive, or is that just a label?

The term "inactive" is misleading. While excipients aren’t meant to treat your condition, research shows many interact with biological systems. Some block enzymes, affect receptor activity, or trigger immune responses. The FDA now acknowledges that "inertness" doesn’t apply to all excipients at all doses.

Can switching to a generic drug cause side effects because of excipients?

Yes. While most generic switches are safe, changes in excipients can alter how quickly a drug dissolves or is absorbed. This can lead to lower effectiveness or new side effects. Cases like Aurobindo’s rejected Entresto generic show that even small changes in lubricants can impact drug release. If you notice a change in how your medication works after switching, report it to your doctor and pharmacist.

Which excipients are most likely to cause problems?

Aspartame, sodium benzoate, propylene glycol, tartrazine, and sulfites have the most documented biological activity. Aspartame can interfere with glucagon signaling. Sodium benzoate affects monoamine oxidase B. Propylene glycol can inhibit monoamine oxidase A. Tartrazine and sulfites are linked to allergic reactions. These aren’t rare-many common medications contain them.

How can I find out what excipients are in my medication?

Check the drug’s package insert or the manufacturer’s website. The FDA requires all inactive ingredients to be listed on the label. You can also ask your pharmacist for the full ingredient list. If you’re switching generics, compare the excipient lists between versions. Even small differences matter.

Are there any excipients I should avoid if I have allergies?

Yes. If you have a known allergy to peanuts, avoid products with peanut oil. If you’re sensitive to dyes, avoid tartrazine or other azo dyes. Sulfites in injectables can trigger asthma attacks. Aspartame can cause headaches or digestive issues in sensitive individuals. Always review the full ingredient list and discuss concerns with your healthcare provider.

So let me get this straight... Big Pharma is hiding toxic junk in our pills and calling it "inactive"? 🤔 They don't even test it?! I knew the system was rigged but THIS?! Aspartame blocking glucagon? Propylene glycol messing with serotonin? That's not science-that's chemical warfare on the masses. 🚨💊 #WakeUpSheeple

The assertion that excipients are biologically inert has been increasingly challenged by empirical research. The FDA's 2022 guidance acknowledges this paradigm shift, and regulatory frameworks must evolve to account for pharmacokinetic interactions at the molecular level. This is not a trivial matter of formulation aesthetics.

OMG I knew it!! I switched to a generic and started getting crazy headaches and my anxiety went through the roof!! I thought it was me but now I get it!! Its the filler!! They swap stuff out and we just suffer!! Why dont they tell us?? This is insane!!

This is serious. I’ve seen patients react differently after generic switches. Not always, but enough times to know it’s not coincidence. We need better tracking. Pharmacists should have access to excipient change alerts. It’s not just about cost-it’s about safety.

The 2020 Science paper’s IC50 overlap with therapeutic plasma concentrations of excipients like sodium benzoate and propylene glycol is statistically significant (p < 0.01). This challenges the assumption of pharmacological neutrality in the IID. Regulatory thresholds must incorporate pharmacodynamic profiling, not just pharmacokinetic equivalence.

Interesting read. I never thought about what’s inside the pill beyond the active ingredient. Makes me wonder how many side effects we just chalk up to "individual variation" when it’s actually the filler. Good to know what to ask for next time I refill a prescription.

This is why America leads in pharma innovation. Other countries overregulate and kill progress. If you can’t handle a little variation in your pills, maybe you shouldn’t be on meds. We don’t need more bureaucracy-we need more trust in our manufacturers.

The casual dismissal of excipient risk reflects a profound epistemological failure in contemporary pharmacology. One cannot assume biochemical neutrality based on historical precedent. The 38 excipients demonstrating biological activity represent not anomalies, but systemic blind spots in regulatory toxicology. The FDA’s reliance on the Inactive Ingredient Database constitutes a form of institutionalized negligence, predicated upon an outdated reductionist model that ignores polypharmacological interactions. This is not merely a regulatory gap-it is a moral failure.

I appreciate this deep dive. As someone who works in drug formulation, I can confirm that novel excipients are increasingly used to improve bioavailability-especially in pediatric and geriatric formulations. The challenge is not just testing them, but predicting how they behave in diverse populations. We need more transparency, not less.

Ah, yes... the classic "they’re hiding something!" narrative. Let me guess-next you’ll tell me water is dangerous because it’s not FDA-approved as a drug? The fact that 99% of people tolerate these excipients without issue doesn’t make them dangerous-it makes them safe. Your fearmongering is statistically irrelevant and emotionally manipulative.

I’ve had this happen to me after switching generics. My blood pressure meds just stopped working. I asked my pharmacist and they showed me the excipient change. Now I always check. Don’t be afraid to ask-your body deserves to know what’s in there.

Funny how we trust the active ingredient but treat the rest like background noise. Meanwhile, we’ll spend hours researching organic kale but swallow pills with 15 unknown chemicals and call it "medicine." Maybe we need to stop being so blasé about what we ingest.

The real issue isn’t just excipient variability-it’s the lack of pharmacogenomic stratification in formulation standards. A concentration of propylene glycol that’s inert in a CYP2E1*1/*1 individual may be toxic in a CYP2E1*5 carrier. We’re treating populations as monoliths while biology is inherently heterogeneous. The FDA’s proposed screening model is a start, but it’s still population-based, not personalized.

In Nigeria, we get generics with no labels at all. This article makes me realize how lucky you are to even have ingredient lists. Knowledge is power.

Of course they’re hiding it. Big Pharma owns the FDA. They don’t want you knowing your pills have aspartame and propylene glycol-same stuff in diet soda and antifreeze. They’re poisoning us slowly. Wake up. This is chemtrail-level cover-up.