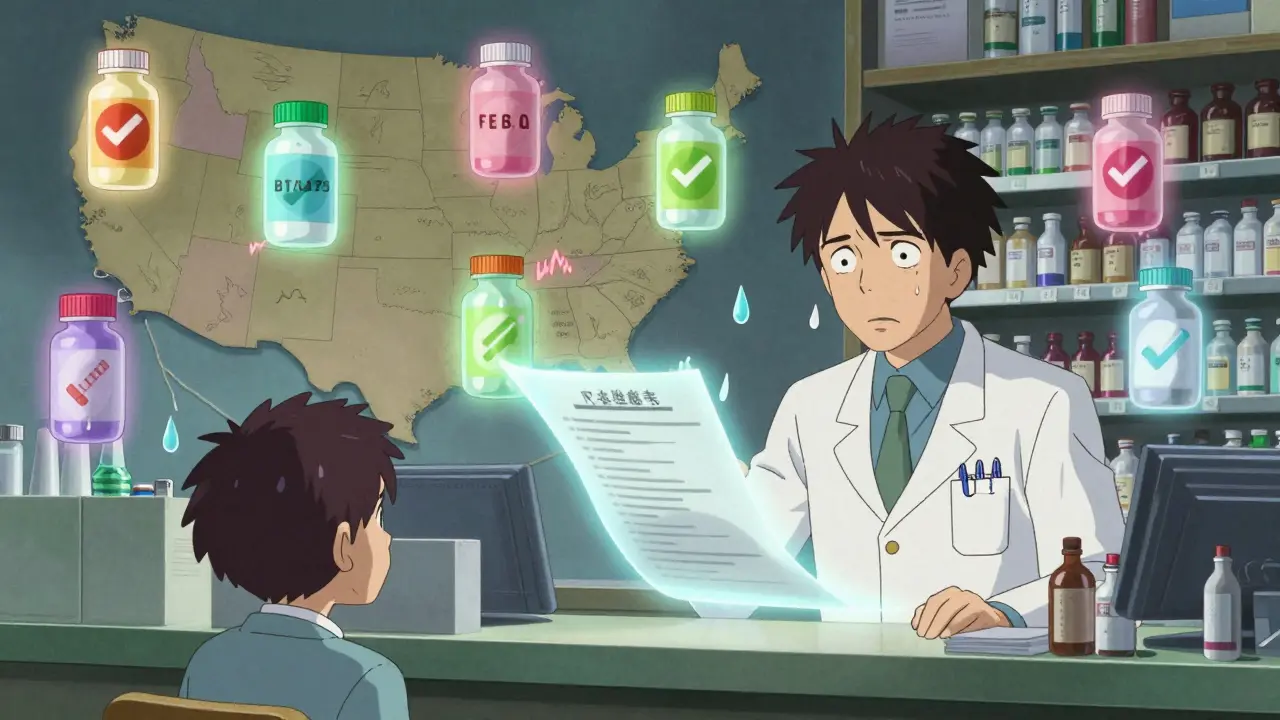

When you pick up a prescription, you might not think about the legal maze behind whether you get the brand-name drug or a cheaper generic. But in the United States, generic substitution isn’t a simple choice-it’s a patchwork of 51 different sets of rules, one for each state and Washington, D.C. Some states force pharmacists to swap in generics unless you say no. Others require you to give clear, written approval. Some let pharmacists substitute without telling you at all. And a few won’t allow substitutions for certain life-critical drugs, no matter the cost savings.

Why Do State Laws on Generic Substitution Even Exist?

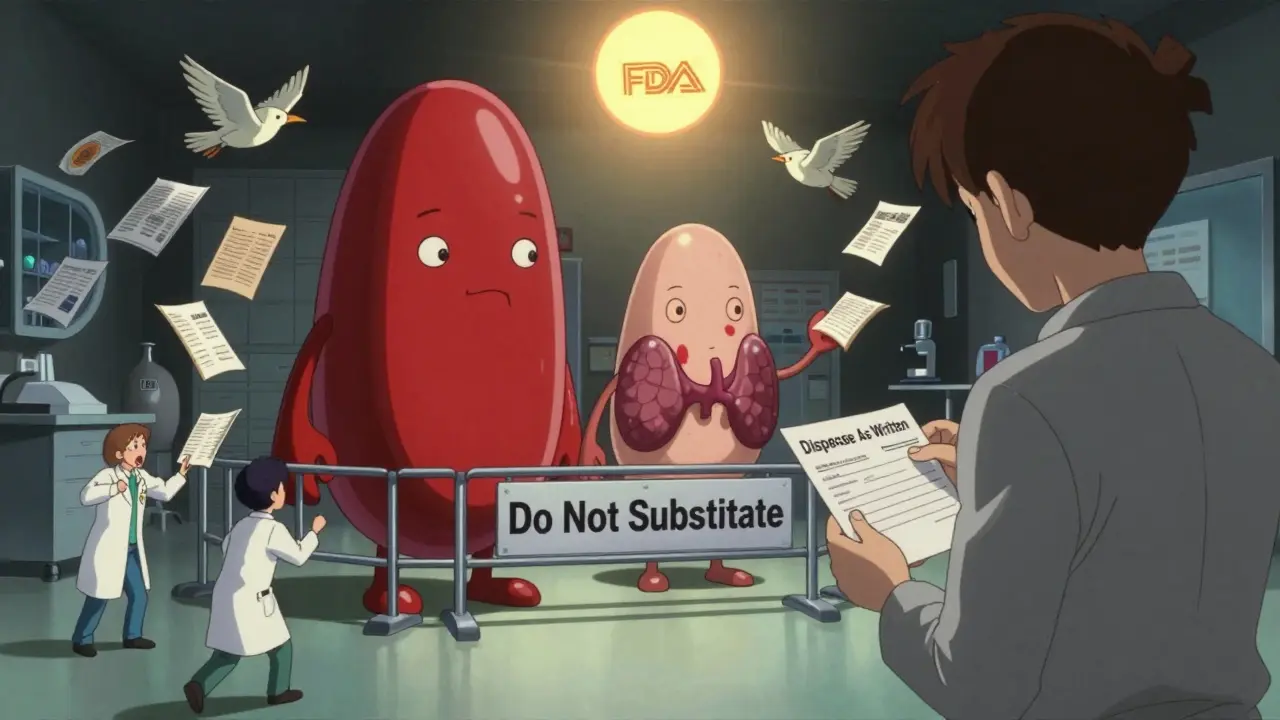

The push for generic substitution started in the 1980s, after Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. That law made it easier for drug companies to bring cheaper versions of brand-name medicines to market. The FDA began listing these generics in the Orange Book, certifying them as therapeutically equivalent. The idea was simple: if a generic works just as well, why pay more? States jumped in to make sure pharmacists could legally make the switch. But here’s the catch: not all drugs are created equal. For drugs like warfarin (a blood thinner) or levothyroxine (for thyroid issues), even tiny differences in how the body absorbs the medicine can cause serious problems. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. So while most states let pharmacists substitute generics freely, 15 states have special lists of NTI drugs that can’t be swapped without the prescriber’s okay. Kentucky, for example, blocks substitution for antiepileptic drugs and digitalis. Minnesota had a case where switching a patient from brand to generic warfarin led to dangerous bleeding-despite the FDA saying they were equivalent.Four Key Ways State Laws Differ

There are four big ways state laws on generic substitution vary-and each one changes how you experience your prescription.- Is substitution mandatory or optional? In 22 states, pharmacists must substitute a generic unless the doctor writes "dispense as written" or you refuse. The other 28 states and D.C. let pharmacists choose whether to swap it or not.

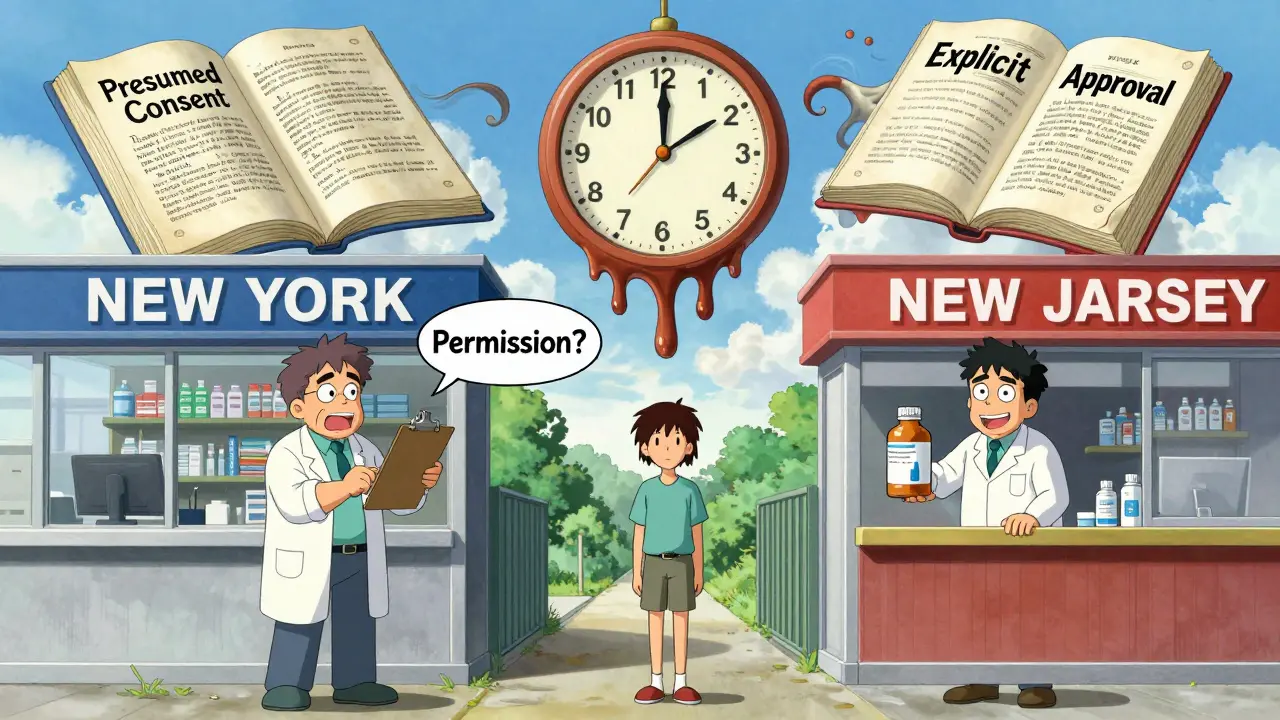

- Do you have to say yes, or just say no? In 32 states, the law assumes you’re okay with the generic unless you speak up-this is called presumed consent. In the other 18, the pharmacist has to ask you outright and get your permission before switching.

- Are you told after the fact? Forty-one states require pharmacists to notify you after the substitution happens, either by handing you a printed notice, calling you, or adding a note to your profile. The rest don’t have to say anything.

- Who’s protected if something goes wrong? In 37 states, pharmacists are shielded from lawsuits if they follow the law exactly. But in the other 13, they could be held liable even if they did everything right.

What Happens When You Cross State Lines?

If you live near a state border-or you’re traveling-you’ve probably run into this: your pharmacy in one state automatically swaps your prescription, but the one across the border asks for your permission. That’s because rules change at the state line. A pharmacist in New York has to ask every patient if they want the generic. In New Jersey, they can swap it without asking unless you tell them not to. Patients who live near borders often get confused. One Reddit user, a pharmacist in the Northeast, wrote: "I have patients who come in from Pennsylvania and freak out because we’re asking if they want the generic. They say, ‘But my pharmacy back home just gave it to me!’" This confusion isn’t just annoying-it’s risky. Chain pharmacies process about 18% of prescriptions that cross state lines. If the system doesn’t catch the right rules for each state, a pharmacist might break the law by substituting where they shouldn’t-or miss a chance to save money where they could.

Biosimilars Are Changing the Game

The rules for generic drugs don’t fully apply to biologics-complex medicines made from living cells, like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis drugs. These have "biosimilar" versions, which are similar but not identical. As of 2023, 49 states and D.C. have laws covering biosimilar substitution. But the rules are even messier. Florida requires pharmacies to create a formulary to make sure any substitution won’t harm patients. Iowa says to stick with the FDA’s Orange Book. Hawaii is the strictest: you need both the doctor’s approval and your own written consent before switching an antiepileptic biosimilar. And in 12 states, the laws were updated in 2023 to match the FDA’s new "interchangeable" designation for biosimilars-meaning they can be swapped without a doctor’s input, just like generics. The problem? There are 49 different rules. The Uniform Law Commission is working on a model law to fix that, but until then, pharmacists have to track 49 different sets of biosimilar rules.Who Wins? Who Loses?

The numbers show the impact. States with mandatory substitution have 12.3% higher generic fill rates for drugs like statins. Presumed consent laws boost substitution by nearly 9%. In Louisiana, where rules are most favorable to substitution, 96% of prescriptions are filled with generics. In Hawaii, where rules are toughest, it’s closer to 85%. Savings are huge. From 2009 to 2019, generic substitution saved the U.S. system $1.7 trillion. Medicaid programs in 27 states saved $1.2 billion a year just from mandatory substitution. Generic drugs now make up 92.5% of all prescriptions filled-up from 78% in 2009. But not everyone benefits. Patients on NTI drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine report feeling worse after a switch. Between 2020 and 2022, the FDA got 217 reports of problems after substitution-89 involved levothyroxine, 53 involved warfarin. Cancer patients are especially wary: 41% of those surveyed by the Life Raft Group said they worry about substitution, and 28% have doctors who explicitly tell them "dispense as written."

What Pharmacists Deal With Daily

Pharmacists are on the front lines. On average, they spend 12.7 minutes per prescription checking state rules, FDA listings, NTI lists, and patient history. That’s more than 100 hours a year per pharmacist just on substitution paperwork. Most pharmacy schools now teach 45 to 60 hours on state substitution laws. Nearly all state licensing exams test this knowledge. And 83% of pharmacy systems now use software that auto-checks state rules, cutting errors by 64%. Still, 7.2% of potential substitutions are refused by patients-sometimes because they don’t understand why the change happened. And the confusion isn’t just among patients. A 2022 survey found that 78% of pharmacists feel overwhelmed by the patchwork of state rules. One said: "I’ve been a pharmacist for 15 years. I still get nervous when a prescription comes in from another state. I don’t know what I’m allowed to do unless I look it up-and I don’t have time to look up 50 different laws."The Future: More Standardization or More Flexibility?

There’s growing pressure to fix this mess. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that if all 50 states aligned their rules, the system could save another $8.7 billion by 2028. Drug manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacy chains all want simpler rules. But patient advocacy groups warn against rushing to standardize. The National Organization for Rare Disorders argues that NTI drugs need special protection-and that a one-size-fits-all rule could hurt people with rare diseases who rely on precise dosing. Right now, the system works because it’s flexible. But it’s also broken. Pharmacists are caught in the middle. Patients are confused. And doctors don’t always know the rules either. The real question isn’t whether generics should be used-it’s whether the U.S. can afford to keep 51 different rulebooks for something as basic as filling a prescription. For now, the answer is yes. But for how long?What You Should Do

If you take a medication that’s critical to your health-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or an antiepileptic drug-always ask your pharmacist: "Is this the same brand I’ve been taking?" If you notice changes in how you feel after a refill, tell your doctor right away. If you’re moving to a new state, check your state’s pharmacy board website. Most have a page on generic substitution laws. And if your doctor writes "dispense as written," make sure the pharmacy honors it. You have the right to know what you’re getting. And in this patchwork system, knowing your rights is the only way to stay safe.Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug to a generic without telling me?

In 32 states, yes-pharmacists can substitute without asking, under what’s called "presumed consent." You’re assumed to agree unless you say no. But in 18 states, they must ask you first and get your approval. In all states, 41 require them to notify you after the substitution, either with a printed notice or an electronic alert. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist what your state requires.

Are generic drugs really as safe as brand-name ones?

For most drugs, yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also be absorbed into the body at the same rate and to the same extent. But for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs-like warfarin, levothyroxine, and some seizure meds-even small differences can matter. That’s why some states restrict substitution for these. If you feel different after a switch, talk to your doctor.

Why do some states block substitution for certain drugs?

Because some medications have a very narrow range between a helpful dose and a dangerous one. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. Even slight changes in how the body absorbs the drug can lead to serious side effects. States like Kentucky, Minnesota, and Hawaii have special lists of these drugs and require the prescriber to approve any substitution. The FDA says all generics are equivalent, but real-world cases have shown that some patients react differently-so states err on the side of caution.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are chemically identical copies of small-molecule drugs, like aspirin or metformin. Biosimilars are copies of complex biological drugs, like insulin or Humira, made from living cells. They’re not exact copies-just very similar. Because of this, biosimilars have stricter substitution rules. Only 12 states allow them to be swapped without a doctor’s approval, and only if the FDA has labeled them as "interchangeable." Most states still require the prescriber’s permission.

Can I refuse a generic substitution even if my state allows it?

Yes. In every state, you have the right to refuse a generic and request the brand-name drug-even if the law allows substitution. You may have to pay more, and your pharmacist might need to contact your doctor to confirm the request. But you cannot be forced to take a generic if you don’t want it. Always say "dispense as written" on your prescription if you want to avoid substitution.

they're watching us through the pills now i swear it

every time i get a generic my phone glitches and my smart fridge starts playing weird music

they're testing something in the fillers

they don't want us to feel too good

in india we get generics for everything and it works fine

the system isn't perfect but it saves lives and money

don't overcomplicate it

the regulatory fragmentation is economically inefficient and clinically inconsistent

standardisation would reduce error rates and administrative burden

the current model is unsustainable

really interesting read

glad we're moving toward more access to affordable meds

keep pushing for clarity, folks

the FDA’s equivalence standard is a statistical fiction

bioequivalence is measured in healthy volunteers, not in patients with comorbidities

the fact that 89 adverse events were tied to levothyroxine substitution proves the system is broken

you’re not getting the same drug

you’re getting a legally approved approximation

so we’ve got 51 rulebooks for a pill

and the pharmacists are the ones getting yelled at when it doesn’t work

and the patients are the ones who die quietly in their beds

and the corporations? They’re sipping champagne on a yacht somewhere

we call this healthcare

funny, right?

how often do pharmacists actually check the state rules manually?

is the software reliable enough to trust?

NTI drugs? Please. The FDA’s bioequivalence thresholds are 80-125% AUC and Cmax

that’s a 45% window for absorption variance

if you’re on warfarin and your INR swings after a generic switch, congrats

you’re just part of the statistical noise

stop being dramatic

why do we even have state laws

its 2024

we have apps that order tacos

but we cant have one rule for pills

someone is making money off this chaos

as a pharmacist in delhi i can tell u

generics save lives daily

in usa you overthink everything

if the med works dont fix it

and if it dont work go back to brand

simple as that

no need for 50 laws

in my family we’ve had three different reactions to levothyroxine generics

one person got dizzy, another lost weight uncontrollably, the third felt fine

it’s not about fear

it’s about individual biology

and if we’re going to treat people like data points, we’ve already lost

the real tragedy isn't the patchwork of laws

it's that the people who need to understand this the most-patients-are the ones least equipped to navigate it

we treat medicine like a puzzle and expect people to solve it while they're sick

maybe the real fix isn't more rules

but more empathy

and fewer acronyms