Emphysema Risk Calculator

Your Emphysema Risk Assessment

Understanding Risk Factors

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (AATD): Severe forms (ZZ genotype) significantly increase risk, even in non-smokers.

MMP12 Variant: Increases susceptibility by roughly doubling the risk of developing emphysema.

Smoking: Heavy smoking increases risk by 5-10 times, especially when combined with genetic factors.

Combined Effects: When genetic risk and smoking coexist, the risk can exceed 30-fold.

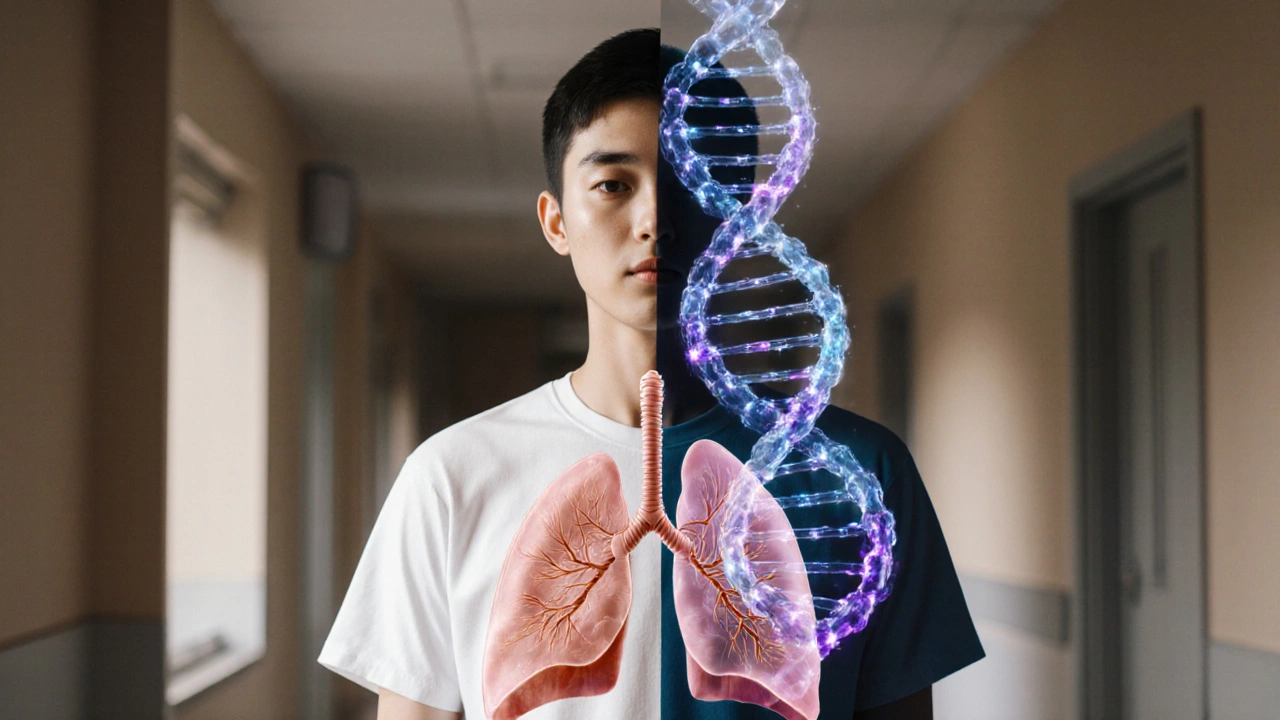

Understanding genetics emphysema connection can feel like piecing together a complex puzzle-genes, smoking habits, and family history all intertwine. This article breaks down the science, shows why certain DNA variants matter, and gives practical steps for anyone worried about their lung health.

- Genetics accounts for 20‑30% of emphysema risk, with specific gene variants doubling susceptibility.

- Alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) remains the most penetrant genetic cause.

- Genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) have identified new risk genes like MMP12 and SERPINA1.

- Environmental factors, especially smoking, amplify genetic risk dramatically.

- Early screening and lifestyle changes can offset genetic predisposition.

What Is Emphysema?

Emphysema is a chronic, irreversible lung disease where the alveoli-the tiny air‑sac balloons-break down, reducing surface area for oxygen exchange. The result is persistent shortness of breath, reduced exercise tolerance, and a higher risk of respiratory infections. Although most people associate it with smoking, research shows that genetics plays a substantial, sometimes hidden, role.

Why Genetics Matters

Genetics refers to the complete set of DNA instructions passed from parents to offspring. Variants in certain genes can influence how lung tissue repairs itself, how it reacts to pollutants, and how efficiently protective proteins are produced. In emphysema, three genetic pathways dominate:

- Deficiency of protective proteins (e.g., alpha‑1 antitrypsin).

- Over‑active proteases that degrade lung matrix.

- Inflammatory signaling that heightens tissue damage.

Each pathway can be tipped by a single nucleotide change, making genetic testing a valuable tool for high‑risk individuals.

Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (AATD)

The single biggest genetic culprit is Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency, a hereditary disorder where the liver fails to produce enough alpha‑1 antitrypsin (AAT), a protein that shields lung tissue from destructive enzymes. People with the ZZ genotype have AAT levels as low as 10‑15% of normal, which can lead to emphysema in their 30s or 40s-even if they never smoked.

Key statistics (European Respiratory Society, 2023):

- ≈1 in 2,500 individuals carry the severe ZZ genotype.

- Up to 60% of ZZ carriers develop emphysema before age 50.

Because AATD follows a clear inheritance pattern, family screening is strongly recommended once a case is identified.

Beyond AATD: Other Genetic Players

Modern GWAS have uncovered several additional risk genes:

- SERPINA1 encodes the AAT protein itself. Common variants (e.g., S allele) modestly lower AAT levels, raising risk by about 1.5‑fold.

- MMP12 codes for matrix metalloproteinase‑12, an enzyme that breaks down elastin. The rs2276109 variant leads to increased MMP12 expression and roughly doubles emphysema susceptibility.

- Genes involved in oxidative stress (e.g., GSTM1 null genotype) impair the lung’s ability to neutralize free radicals from smoke or pollution.

- Inflammatory regulators such as IL‑6 and TNF‑α promoter polymorphisms amplify chronic airway inflammation.

Each of these variants contributes a small effect, but together they can push an individual over the threshold for disease.

How Environmental Exposures Amplify Genetic Risk

Genetics alone rarely causes severe emphysema; it’s the interaction with inhaled toxins that seals the deal. The most powerful synergy is with cigarette smoking.

| Factor | Relative Risk Increase | Typical Onset Age |

|---|---|---|

| Severe AATD (ZZ genotype) | 10‑15× | 30‑45 years |

| Moderate SERPINA1 S allele | 1.5× | 40‑60 years |

| Heavy smoking (>20 pack‑years) | 5‑10× | 40‑70 years |

| Occupational dust (coal, silica) | 2‑3× | 50‑70 years |

| Combined AATD + smoking | >30× | 30‑50 years |

The table makes clear why a smoker with a modest genetic variant still faces a steep risk-smoking acts as a catalyst, accelerating tissue breakdown.

Who Should Consider Genetic Testing?

Not everyone needs a DNA panel, but certain groups have a high yield:

- Individuals diagnosed with emphysema before age 50.

- Patients with a strong family history of early‑onset lung disease.

- Never‑smokers who present with classic emphysema imaging.

- People with unexplained liver disease-AATD often affects both liver and lung.

Testing typically involves a blood draw or cheek swab, followed by analysis of SERPINA1, MMP12, and a panel of GWAS‑identified SNPs. Results are usually returned within 2‑3 weeks.

Practical Steps After Learning Your Risk

Finding a high‑risk genotype can be scary, but it also opens a path to prevention:

- Quit smoking or avoid tobacco exposure entirely. Even light smoking adds a disproportionate risk for carriers.

- Consider AAT augmentation therapy if you have severe AATD. Intravenous purified AAT can slow lung decline, as shown in the 2022 RAPID trial.

- Engage in regular pulmonary rehabilitation-exercise improves lung capacity and reduces breathlessness.

- Schedule annual low‑dose CT scans to monitor early changes, especially if you’re a carrier.

- Inform close relatives. First‑degree family members have a 50% chance of sharing the same risk alleles.

These actions are supported by guidelines from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 2024) and the British Thoracic Society.

Future Directions: Personalized Medicine on the Horizon

Research is fast‑tracking toward gene‑editing and RNA‑based therapies that could correct SERPINA1 mutations at the source. Early‑phase CRISPR trials in mice have restored normal AAT levels and halted emphysema progression.

Meanwhile, polygenic risk scores (PRS) that bundle dozens of SNPs into a single numeric value are being validated for clinical use. A PRS above the 90th percentile could soon trigger automatic referral to a lung specialist.

For now, the best strategy remains a combination of genetic insight, lifestyle modification, and regular medical surveillance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a non‑smoker develop emphysema?

Yes. About 15‑20% of emphysema cases occur in never‑smokers, and genetic factors-especially Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency-are the main drivers in these individuals.

How is AATD diagnosed?

Diagnosis begins with a blood test measuring AAT levels. If low, a genotype test for the SERPINA1 gene (looking for Z and S alleles) confirms the diagnosis.

Is there a cure for emphysema?

Currently there is no cure, but treatments-such as bronchodilators, pulmonary rehab, and for AATD patients, AAT augmentation-can slow progression and improve quality of life.

Should my children be tested if I have AATD?

Yes. Since AATD is autosomal recessive, each child has a 25% chance of severe disease (ZZ) and a 50% chance of being a carrier. Early detection enables monitoring and lifestyle guidance.

What lifestyle changes help if I have a genetic risk?

Quit smoking, avoid second‑hand smoke, limit exposure to occupational dust, maintain a healthy weight, and engage in regular aerobic exercise. These steps reduce inflammation and improve lung reserve.

People love to point at DNA like it’s a magic script, but the lungs still have to breathe air that we shove into them. The ZZ genotype of AATD is a real danger, yet most folks never hear about it until a doctor mentions it. Even a modest MMP12 variant can double the odds, which is scary if you’re already lighting up. So yeah, genetics matter, but they’re only part of the story. Think of it like seasoning – it can make a dish better or worse, but the ingredients still have to exist.

Wow, so your metaphor is culinary, huh? If the genetics are the spice, smoking is the grease fire you set in the kitchen. No wonder the risk skyrockets when you mix the two. Pretty much a recipe for disaster, and not the tasty kind.

Honestly, it’s wild how many people think smoking is the only villain. The data on SERPINA1 S allele shows even light smokers get a boost in risk. It’s like getting a side‑quest you didn’t ask for.

Indeed!; The point is, if you already have a genetic ticket, smoking just hands you a fast‑track pass to serious trouble; ; It's like driving a car with a broken brake and stepping on the gas! ;

i think it’s cool that they gave a calculator but most of us wont even think to use it lol. the zz genotype is rare but if u got it u should be extra careful . also the mmp12 thing is new to me .

👍 Great point! If you’ve got the ZZ genotype, quitting smoking is the single biggest power‑move you can make. 👏 And don’t forget those annual low‑dose CT scans – they catch changes early. 🌟

the relationship between genetic variants and lung degradation is a nuanced tapestry, where each thread influences the overall resilience of pulmonary tissue. while the zz allele dramatically lowers aat levels, the s allele merely nudges risk upward, yet its prevalence makes it clinically relevant. nuances matter.

Sure, nuances are key :) but at the end of the day, if you’re a carrier you still have agency – quit smoking, stay active, get screened. -_-

From a translational genomics standpoint, the polygenic risk scores integrating rs2276109 (MMP12) alongside SERPINA1 variants provide an additive risk matrix that can be operationalized in primary care workflows. Leveraging electronic health records to flag high‑risk genotypes could streamline referral pathways to pulmonology and enable preemptive lifestyle interventions. Moreover, the synergy between oxidative stress loci (e.g., GSTM1 null) and environmental particulate exposure underscores the need for occupational health vigilance. This is not just academic; it translates into actionable precision medicine protocols.

Exactly! The more we push that data into clinics, the more patients can get personalized action plans before the disease even shows up. It’s empowering.

Genetics and emphysema are often discussed in isolation, but the real story is a complex interplay that spans biology, environment, and lifestyle. First, the ZZ genotype of alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency reduces protective AAT levels to a fraction of normal, leaving elastin fibers vulnerable to unchecked protease activity. Second, the MMP12 variant upregulates a metalloproteinase that directly degrades alveolar walls, effectively accelerating the same destructive process. Third, even modest polymorphisms in the SERPINA1 S allele can tip the balance, especially when combined with chronic irritants. Fourth, smoking serves as a catalyst, delivering a barrage of oxidants that both increase protease expression and impair antioxidant defenses. Fifth, occupational exposures such as silica or coal dust add another layer of insult, compounding the genetic predisposition. Sixth, epidemiological data show that individuals with any of these risk alleles develop emphysema on average a decade earlier than those without. Seventh, family history remains a powerful predictor because it captures both shared genetics and often shared environmental habits. Eighth, early screening with low‑dose CT or spirometry can detect subtle declines before symptoms become disabling. Ninth, intervention strategies like AAT augmentation therapy have demonstrated slowed lung function decline in severe ZZ carriers. Tenth, smoking cessation, even after decades of use, substantially reduces the rate of progression, underscoring the plasticity of risk. Eleventh, lifestyle modifications-regular aerobic exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding secondhand smoke-further buttress lung resilience. Twelfth, emerging polygenic risk scores promise to synthesize dozens of small‑effect variants into a single actionable metric. Thirteenth, gene‑editing technologies such as CRISPR are being explored in animal models to correct SERPINA1 mutations at the source. Fourteenth, patient education is essential; many at‑risk individuals remain unaware of their genetic status until a severe event forces evaluation. Fifteenth, clinicians should adopt a multidisciplinary approach, involving genetic counselors, pulmonologists, and primary care providers to craft individualized care plans. Finally, the convergence of genetic insight, early detection, and targeted therapy offers a hopeful trajectory for reducing the burden of emphysema in the coming decades.

While the preceding exposition is indeed comprehensive, I would like to emphasise the importance of adhering to the GOLD 2024 recommendations when managing patients with identified genetic risk factors. A structured follow‑up schedule, incorporating spirometric assessment at six‑month intervals, is advocated to monitor disease trajectory. Additionally, the integration of multidisciplinary care pathways ensures that genetic counselling, pulmonary rehabilitation, and psychosocial support are provided in a cohesive manner.

It is absolutely imperative, and utterly shameful, that society continues to ignore the moral responsibility we have toward individuals with genetic predispositions to emphysema; we must prioritize early screening and robust public health campaigns! The negligence exhibited by policymakers is simply indefensible!;

Honestly, this whole "genetics" excuse is just a convenient way for the liberal agenda to distract us from the real issue-people need to take personal responsibility, stop smoking, and stop blaming their DNA! America will be stronger when we focus on individual choice over victimhood!;

There's a hidden layer to the whole genetics-emphysema narrative that most mainstream articles conveniently skip over, and that hidden layer is the coordinated effort by major tobacco corporations to fund research that downplays the role of environmental toxins while inflating the significance of obscure gene variants. Look at the funding trails-big pharma and tobacco giants funnel millions into studies that cherry‑pick data, ensuring that the public perception leans toward believing that "it's just your genes" when in reality the chemicals in cigarettes are engineered to amplify protease activity in a way that specifically exploits known genetic weaknesses. This is not speculation; the leaked documents from the 2018 conference show a clear agenda to shift liability away from product safety and toward a narrative of personal genetic destiny. Moreover, the rise of direct‑to‑consumer genetic testing kits has created a market where people are sold the illusion of control, while the same companies have vested interests in keeping smoking rates high because it drives demand for their "risk mitigation" services. The interplay between corporate lobbying, selective scientific publishing, and public health messaging forms a complex web that systematically obscures the truth. In short, don't be fooled by the surface-level emphasis on genetics; dig deeper and you'll see that the biggest threat is the manipulation of data by entities that profit from disease.

Indeed, critical thinking is essential when evaluating such claims.

the shadows of deception stretch far and wide, and those who trust the glossy brochures may never see the strings being pulled behind the scenes

i dont no why peopl keep ignorng the smoking factor

Yo, even if your DNA's got a bad rap, you can still kick that habit and give your lungs a fighting chance-think of it as flipping the script on destiny!