When your lungs start to stiffen and scar, breathing doesn’t just get harder-it becomes a daily battle. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) isn’t one condition. It’s a group of over 200 disorders that slowly destroy the delicate tissue between your air sacs, turning flexible lung tissue into rigid, scarred tissue. This isn’t just about getting winded after climbing stairs. For many, it means oxygen tanks at night, canceled plans, and the fear that every cough could be the start of something worse.

What Exactly Is Happening in Your Lungs?

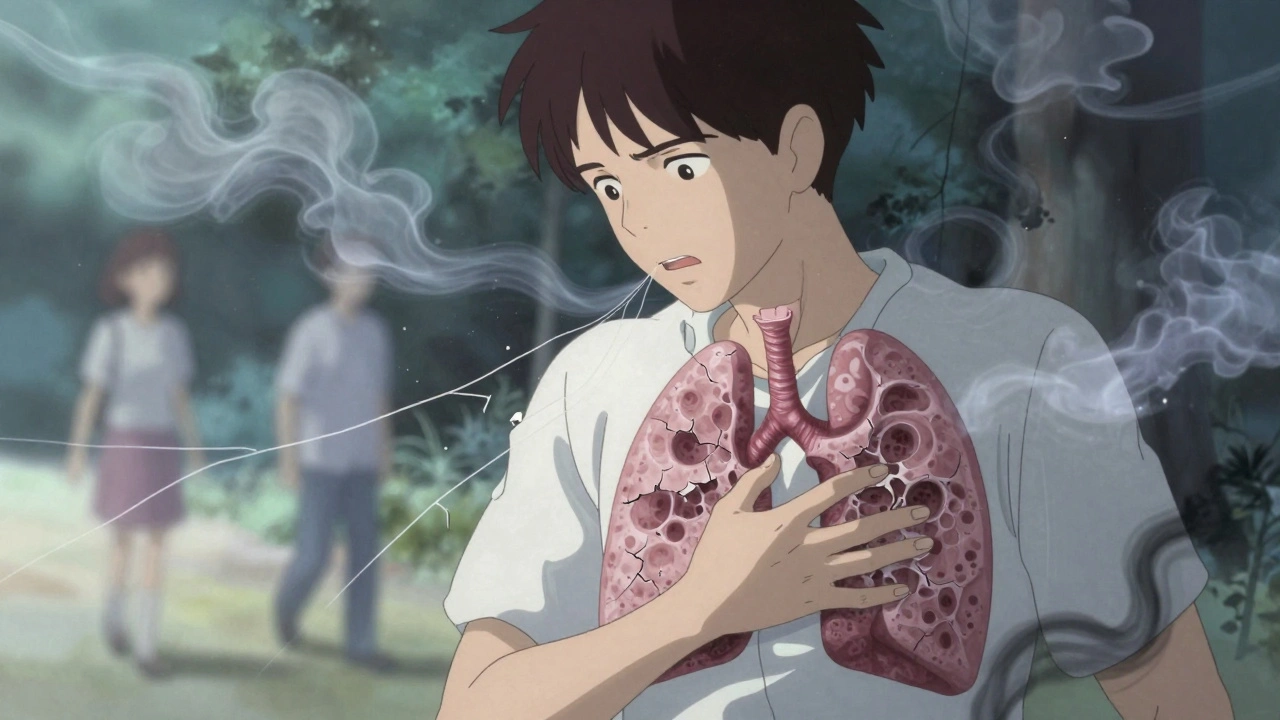

Your lungs aren’t just sacks of air. Between the tiny air sacs-called alveoli-is a thin layer of tissue called the interstitium. It’s where oxygen slips into your blood and carbon dioxide leaves. In healthy lungs, this layer is thinner than a sheet of paper. In ILD, it thickens. Fibrosis builds up. Scar tissue replaces the stretchy, sponge-like structure your lungs need to work properly.

That’s why breathing feels like trying to inhale through a clogged straw. Your lungs can’t expand fully. Oxygen can’t cross into your bloodstream as easily. That’s why most people with ILD first notice shortness of breath during activity-walking to the mailbox, carrying groceries, even talking. It doesn’t come on suddenly. It creeps in. Many think it’s just aging or being out of shape. By the time they see a specialist, the damage is already advanced.

Doctors use high-resolution CT scans to see this scarring. A normal scan shows smooth, fine lines between air sacs. An ILD scan looks like a spiderweb gone wrong-thick, tangled, uneven. That’s fibrosis. And once it’s there, it doesn’t go away.

Who Gets ILD-and Why?

ILD doesn’t pick favorites, but it does have patterns. The most common form is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), making up 20-30% of all cases. "Idiopathic" means no clear cause. It mostly affects people over 60, especially men who smoked. But ILD can also come from other places:

- Autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or scleroderma-about 15-20% of ILD cases

- Environmental exposure to asbestos, silica dust, or bird feathers (farmer’s lung)

- Medications-some chemotherapy drugs, heart medications, and even certain antibiotics can trigger it

- Radiation therapy to the chest, often years after treatment

- Sarcoidosis, where immune cells form clumps in the lungs

Some forms, like sarcoidosis, can clear on their own. Others, like IPF, keep getting worse. And here’s the hard truth: once scarring happens, you can’t undo it. The goal isn’t to reverse it-it’s to slow it down before it steals your breath.

How Do You Know It’s ILD and Not Something Else?

Most people see their doctor because they’re out of breath. But doctors often mistake ILD for asthma, COPD, or just getting older. A 2023 study found that nearly 80% of ILD patients had been misdiagnosed at least once. The average time from first symptoms to correct diagnosis? Over a year.

Here’s what actually points to ILD:

- Dry cough that won’t go away-no mucus, no relief

- Crackling sounds in the lungs when a doctor listens with a stethoscope-like Velcro being pulled apart

- Clubbed fingers-the tips widen and round out, nails curve downward

- Low oxygen levels during simple tasks, even if you feel fine at rest

Testing is key. Pulmonary function tests show your lungs can’t hold as much air (low FVC) and struggle to transfer oxygen (low DLCO). But the real game-changer is the high-resolution CT scan. It shows the exact pattern of scarring. And because ILD has so many forms, doctors now use a multidisciplinary team-pulmonologists, radiologists, and sometimes lung biopsies-to get the diagnosis right.

Treatment Options: Slowing the Scarring

There’s no cure. But there are tools to fight the progression.

The two main drugs approved for IPF-nintedanib (Ofev®) and pirfenidone (Esbriet®)-aren’t magic bullets. But they do something powerful: they cut the rate of lung function decline by about half. In clinical trials, patients on these drugs lost 50% less lung capacity over a year than those on placebo.

But they come with side effects. Pirfenidone causes nausea, dizziness, and extreme sun sensitivity-you can’t even sit outside without burning. Nintedanib often leads to diarrhea and liver enzyme changes. Most patients need dose adjustments. But for many, the trade-off is worth it.

For non-IPF ILD, these drugs help less. That’s a big gap. If your ILD is tied to rheumatoid arthritis, your doctor might try immunosuppressants like mycophenolate or azathioprine. If it’s from an infection or exposure, removing the trigger can stop the damage.

And now, there’s a new option: zampilodib, approved by the FDA in September 2023. It’s the first new antifibrotic in nearly a decade, showing a 48% reduction in lung function loss. It’s not for everyone yet-but it’s a sign that progress is happening.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Reclaiming Your Life

Medications don’t fix everything. That’s where pulmonary rehab comes in. It’s not fancy. It’s walking on a treadmill with oxygen, doing arm exercises, learning breathing techniques, and getting coached on energy conservation.

Studies show that after 8-12 weeks of supervised rehab, people gain 45-60 meters on the 6-minute walk test. That might not sound like much, but for someone who used to stop after 100 feet, it means walking to the end of the driveway without stopping. It means going to a grandchild’s recital without needing a chair halfway through.

It also reduces hospital visits by 30%. Why? Because you learn to recognize the warning signs of a flare-up-sudden worsening of breathlessness, fever, or a change in cough-and act fast.

And here’s something many don’t talk about: rehab helps your mental health. Anxiety from constant breathlessness is real. Being around others who get it? That helps more than you’d think.

Oxygen, Lifestyle, and the Hard Choices

When your blood oxygen drops below 88% at rest, supplemental oxygen becomes necessary. Many resist it-fear of looking sick, stigma, inconvenience. But oxygen isn’t a sign of defeat. It’s a tool that lets you stay active, sleep better, and protect your heart.

Modern portable oxygen systems are lightweight. Some fit in a backpack. Others are even small enough to carry in a purse. You don’t have to be housebound.

Smoking? Stop. Now. Even if you’ve smoked for 40 years, quitting can slow the decline. Avoid secondhand smoke, dust, and chemical fumes. Get your flu and pneumonia shots. Infections can trigger sudden, life-threatening worsening of ILD.

And nutrition matters. Many with ILD lose weight because breathing takes so much energy. Eating small, frequent meals rich in protein and calories helps. A dietitian who understands lung disease can make a real difference.

The Future: Better Tests, Better Treatments

Right now, doctors are using blood tests to spot early signs of ILD. One test looks for a genetic marker called MUC5B. If you have it, your risk of developing IPF goes up by 85%. That means screening high-risk groups-like long-term smokers or people with autoimmune diseases-could catch ILD before it’s visible on a scan.

Artificial intelligence is stepping in too. At Mayo Clinic, AI algorithms now analyze CT scans with 92% accuracy-better than many radiologists. That means faster, more precise diagnoses.

Over 25 clinical trials are testing new drugs: stem cell therapies, gene-targeted treatments, even drugs that aim to repair scar tissue instead of just slowing it. The goal? Not just to extend life, but to let people live better with it.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you love has unexplained shortness of breath, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s just age. Ask for a referral to a pulmonologist-and specifically ask if they have experience with ILD. Most community hospitals don’t. But academic centers do.

Keep a symptom journal. Note when you get winded, how far you walk, what helps or makes it worse. Bring it to your appointment. It’s more helpful than you realize.

And if you’re already diagnosed: join a support group. The loneliness of chronic breathlessness is heavy. You’re not alone. Thousands are walking this path. And with the right care, many are still working, traveling, and enjoying life-even with oxygen.

ILD is serious. But it’s not a death sentence. It’s a challenge-and with the right tools, you can still live well.

Is interstitial lung disease the same as pulmonary fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis is a type of interstitial lung disease (ILD), but not all ILD is pulmonary fibrosis. ILD is the umbrella term for over 200 conditions that cause scarring in the lung tissue between the air sacs. Pulmonary fibrosis specifically refers to the scarring (fibrosis) itself. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common and most aggressive form of ILD, but other types-like those caused by autoimmune disease or asbestos-can also involve fibrosis. So all pulmonary fibrosis is ILD, but not all ILD results in the same kind of scarring.

Can you live a normal life with interstitial lung disease?

Yes, many people do-but "normal" changes. With early diagnosis and treatment, it’s possible to maintain daily activities, work, and social life for years. Pulmonary rehab, oxygen therapy, and medications like nintedanib or pirfenidone help slow progression. Some people live 5-10 years or more after diagnosis, especially if their ILD is linked to a treatable cause like autoimmune disease. The key is managing symptoms, avoiding triggers, and staying active within your limits. It’s not the life you planned, but it can still be meaningful.

How fast does interstitial lung disease progress?

Progression varies wildly. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) typically worsens steadily, with lung function declining 150-300 mL per year on average. Some people decline slowly over years; others have sudden, rapid worsening called acute exacerbations. In contrast, ILD caused by rheumatoid arthritis may progress slowly, and sarcoidosis often improves on its own. Environmental causes like asbestosis can take decades to advance. There’s no single timeline-it depends on the subtype, age, smoking history, and how early treatment starts.

Are the medications for ILD worth the side effects?

For many, yes. Nintedanib and pirfenidone reduce lung function decline by about half over a year. Side effects like nausea, diarrhea, or sun sensitivity are common, but most can be managed with dose adjustments or supportive care. Many patients report that the benefit-being able to walk farther, breathe easier, and avoid hospital visits-outweighs the discomfort. If side effects are too severe, your doctor can switch you to another drug or try a lower dose. The alternative-doing nothing-means faster loss of lung function and reduced quality of life.

Can you prevent interstitial lung disease?

You can’t prevent all forms, especially idiopathic ones. But you can reduce your risk. Quit smoking. Avoid exposure to dust, fumes, and chemicals at work-use masks and ventilation. If you have an autoimmune disease like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, keep it under control with your rheumatologist. Get vaccinated for flu and pneumonia. Early detection matters too: if you’re over 60, have a history of smoking, or have unexplained breathlessness, ask for a lung CT scan. Catching ILD early gives you the best shot at slowing it down.

Man, this post hit home. My dad was diagnosed with IPF two years ago, and I swear, the day we got that CT scan, it felt like the world stopped. He’s been on nintedanib since, and yeah, the diarrhea’s a nightmare-but he’s still walking the dog every morning, and that’s everything. I used to think lung disease meant sitting around waiting to die. Turns out, it’s more like learning to breathe again, one step at a time. Pulmonary rehab saved his sanity, honestly. The group there? They’re his new family. If you’re reading this and scared? Don’t be. Just get moving. Even if it’s slow.

Another liberal hyping up another chronic illness to push more government-funded treatments. Nobody’s forcing you to take these drugs. Quit smoking, stop eating carbs, and get off your couch. You don’t need a $10,000/month pill to breathe. This is just another way for Big Pharma to bleed the system.

Kevin’s comment is exactly why I keep coming back to this community. For everyone else who’s scared or confused: yes, the side effects of pirfenidone are brutal-sunburns that feel like you’ve been boiled alive, nausea that turns breakfast into a war zone. But here’s what no one tells you: the first time you walk from your bedroom to the kitchen without stopping? That’s not just physical. It’s emotional victory. I’ve seen patients cry in rehab because they finally held their grandchild without gasping. That’s worth every pill. And if you’re on oxygen? Good. It’s not a crutch-it’s your freedom. Modern portable units weigh less than a water bottle. You can hike, travel, even dance. Don’t let stigma steal your joy.

Wow. Just... wow. 😒 You’d think after 200+ years of modern medicine, we’d have something better than ‘take this pill that makes you sick to slow down the thing that’s killing you.’ Like, congrats, we’ve turned death into a slow drip… with side effects. 🤦♀️

Did you know the FDA approved zampilodib because of a secret deal with Big Pharma? 🤫 They’re hiding the real cause-5G towers and EMF radiation. I’ve been tracking my oxygen levels with my Apple Watch and the drops always happen near cell towers. Also, your doctor is lying to you. The real cure is magnesium chloride and essential oils. 🌿💧 #ILDtruth #StopTheLie

While the clinical data regarding antifibrotic agents such as nintedanib and pirfenidone demonstrate statistically significant reductions in the rate of decline in forced vital capacity, one must not overlook the profound psychosocial dimensions of chronic respiratory disease. The existential burden of progressive dyspnea, compounded by societal stigma surrounding oxygen dependency, necessitates a holistic, multidisciplinary approach that integrates palliative care principles into routine pulmonary management. Moreover, the absence of biomarkers for early detection remains a critical gap in translational research.

Life is just a breath, man. We all die slowly. The lungs? Just the first to whisper it. 🤔 The real question isn’t how to slow the scar… it’s how to love while you’re still breathing. 🌊

It is a fundamental error to conflate the symptomatic management of interstitial lung disease with its purported cure. The administration of antifibrotic agents does not constitute therapeutic success; rather, it represents a palliative compromise. Furthermore, the assertion that pulmonary rehabilitation confers meaningful functional improvement lacks sufficient longitudinal validation. One must question the epistemological basis of these claims in light of the absence of randomized controlled trials with mortality endpoints.

Just got my first oxygen tank. Looked like a monster. Now I take it to the park. Kids ask if it’s a jetpack. I say ‘yeah, and I’m flying to Mars next week.’ They believe me. Best therapy ever. 🤘

As an Aussie who’s seen this up close, I gotta say-your healthcare system’s got it right. We’ve got subsidized oxygen, free rehab, and doctors who actually listen. I met a bloke in Melbourne who still does bushwalking with his tank strapped on. Said, ‘If I can climb a hill with this thing, I’m not losing.’ That’s the spirit. Keep going. We’re all in this together.

What I love about this post is how it doesn’t sugarcoat it. You’re not broken-you’re adapting. And that’s the quiet revolution here. It’s not about curing. It’s about reclaiming. I had a friend who stopped going to family dinners because she couldn’t breathe through the laughter. After rehab? She’s back. Laughing harder than ever. That’s not just medicine. That’s magic. Keep showing up. Even if it’s just to breathe.

Stop glorifying this. You’re not ‘living well’ with a scarred lung-you’re surviving on a countdown. These drugs are just buying time so pharmaceutical CEOs can keep raking in billions. And don’t get me started on ‘pulmonary rehab’-it’s just a fancy way of saying ‘go walk until you collapse and feel better about it.’ This system is rigged. You’re not supposed to win. You’re supposed to be grateful for the crumbs.